Healthy Soul Food Inspires Wellness while Preserving Culture

Recently, I had an engaging conversation with Chef Anthony Head, Sr. The 45 years-old African-American chef founded Chicken Head’s, which presently operates as a ghost kitchen in Kettering, a suburb of Dayton, Ohio. (see “Chef Anthony T. Head Dishes on His Passionate Affair … with Cooking”) Involved in the uniqueness of this type of eatery is that its presence is primarily online and transactions are digital.

Image of Chef Anthony T. Head, Sr. is sourced from his Facebook page, December 14th, 2024 by Karen D. Brame

The recent win of his “Medusa Sandwich” being named “Best Chicken Sandwich in Dayton” brought to mind several other soul food spots in the city. These include Mz. Jade’s Soul Food, De’Lish and Soul Food Carry Out. The connections between these four illustrate close-knit ties of community. Mz. Jade’s is located in West Social Tap and Table, a food hall where De’Lish previously called home. De’Lish is now a food truck operated by its founder Jasmine Brown. Soul Food Carryout is led by Chef Mark Brown, who premiered as Executive Chef at De’Lish, where, by the way, Chef Head was his Sous Chef.

Chef Head and I passionately discussed soul food. Our conversation ran the gamut, including its origins, impact on the African-American community and the contemporary movement to make it healthier to consume, allowing one of our greatest cultural traditions to flourish.

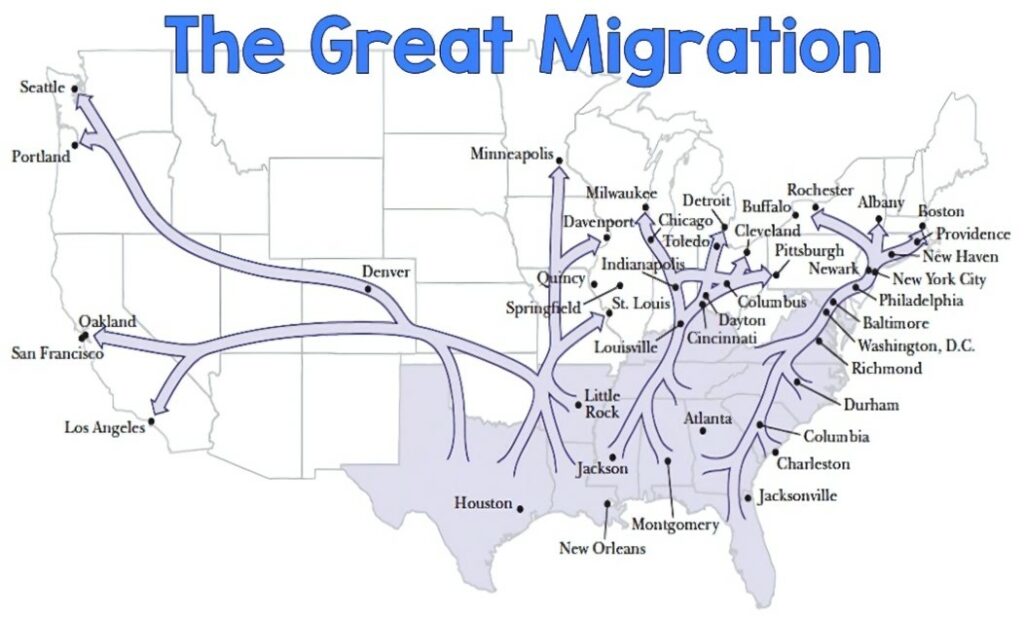

Soul food is a cuisine created by African-Americans who lived primarily in Alabama, the Carolinas, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi. During The Great Migration (1910 – 1970), more than six million African-Americans fled the rural South. The primary reasons for this mass movement, according to the National Archives article in “African American Heritage”, were to “escape racial violence, pursue economic and educational opportunities, and obtain freedom from the oppression of Jim Crow.”

These Black migrants settled in major urbanized cities throughout the country. Among their possessions was their knowledge of food unique to their historic experiences.

Image of “The Great Migration” map is sourced from Students of History website, December 14th, 2024 by Karen D. Brame

According to Vanessa Hayford in “The Humble History of Soul Food”, retainment of their African roots to specific crops and animals allowed them to create delicious foods that were shared at gatherings. Dining on soul food still offers African-Americans the opportunity to hold on to their cultural practices and each other.

Soul food is stereotyped to reference the unhealthiest foods, especially pork. As Pork Checkoff declared on its website, “No other animal provides a wider range of products than the hog. The amazing utility of the hog has motivated the saying, ‘We use everything but the oink.’”

Long before this declaration, African-Americans had been forced to do the same but with the poorest parts of a pig. When you view a butcher’s chart, you readily relate that its scraps, especially those parts that are low on its body, have been staples in traditional soul food. Several are listed under the “Soul Food” entry on the African-American Registry website are “chitterlings/chitlins, cracklins, fatback, ham hocks, hog maws, hog head cheese, pig’s feet and ribs.”

Chef Head affirmed a truth in this stereotype. He noted, “Modern soul food in America’s only deemed ‘unhealthy’ because of its use of processed cooking oils, cheeses, fried, smoked or otherwise processed meats. Historically, it was the creative use of food scraps to provide sustenance to those who needed its caloric density to survive.” Frequent consumption of low nutrition foods, often fried, and containing high amounts of fat, salt and sugar, has had terrible impacts on the Black community.

In the United States, African-Americans rank among the top of the list of chronic illnesses, notably cancer, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, obesity and stroke, for myriad reasons. These include the socio-economics of poverty such as food apartheid; abundance of fast-food eateries, and mini-marts stocked with expensive junk food and outdated staples; minimal access to affordable healthy food; overeating; as well as lack of physical exercise and/or labor.

The ethnographic study, “Culture and Food Practices of African-American Women with Type 2 Diabetes”, of the National Library of Medicine profiled twenty African-American women, ages thirty-five to seventy years old with the illness. It examined selection of food and dining practices at home and in social gatherings; the influence of social interactions on food choices; and cultural significance and values placed on food. Among its results were that these women found it difficult to modify their eating habits because of their “emotional dedication to the symbolism of food derived from traditional cultural food practices passed down from generation to generation.”

The American Heart Association warned in its “Black People, Heart Disease and Stroke” article published on its website that the risks of heart disease being the number 1 killer and stroke being the number 5 killer are even greater for African-Americans. Accounting for the pervasive influences of historic racism, rampant discrimination and inequitable societal constructs, the Association asserted, “Among them are adverse social determinants of health, the conditions in which a person is born and lives. The determinants include lack of access to health care and healthy foods, and other societal issues.”

Contrary to popular belief, traditional soul food can be healthy because it contains many vegetables. Also included under “Soul Food” by the Registry are “black-eyed peas, butter beans, collard greens, lima beans, mustard greens, okra, red beans, succotash, sweet potatoes, turnip greens and yams.”

Chef Head emphasized that soul food “is inherently healthy when made with wholesome ingredients and consumed in appropriate quantities when balanced against daily activity. Its ancestral roots are essentially vegetarian, with meat mainly used for flavorful broths and seasoning and vegetables, especially root vegetables and leafy greens, are the “center” of the plate item. Stews like Gumbo, can be fortified with more roasted vegetables in lieu of processed and smoked meats. In cuisines throughout West Africa, rice, plantains, cassava and yams typically provide alternative complex carbohydrates that are equally as nourishing as they are satiating.”

African-American physician Alonzo Patterson III, MD, Chief Medical Health Equity Officer at Dayton Children’s Hospital offered his insight. Conversing on an autumn day, he asserted that, “Most soul food is not unhealthy because it is vegetable-centered. What makes traditional soul food unhealthy are things added to it.

African-Americans are innovative and have had to make do with foods that were accessible, in the past and presently. Much of what was eaten were vegetables, and we learned to prepare them in a variety of ways. Part of this preparation was contingent upon ways to store food. For example, some make neckbones and sauerkraut because it lasted longer than cabbage.”

Image of Alonzo Patterson III, MD is sourced from PriMed Physicians website on December 12th, 2024 by Karen D. Brame.

Referencing the health issues African-Americans are at high risks for and their connection with traditional soul food, Dr. Patterson acknowledged these issues and was adamant that with modifications, African-Americans could still enjoy this cuisine. Emphasizing that Black people are not monolithic, he encouraged better choices for optimum health be made. He advised, “We need to return to the art of cooking our own food daily. When it comes to soul food, we can adapt it to be healthier and not hurting.”

The nouveau soul food movement has championed healthy versions of traditional soul food. Discussed in the Museum of UnCut Funk article, “An Illustrated History of Soul Food”, chefs, such as Marcus Samuelsson and Bryant Terry; culinary historians, including Toni Tipton-Martin; and tastemakers like B. Smith, have created countless adaptations since the 1990s. These range from baking instead of frying as well as using herbs and spices in lieu of salt to developing vegan editions and growing Afro-vegan gardens.

In Terry’s Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh African, Caribbean & Southern Flavors Remixed, African-American culinary historian Michael W. Twitty highlighted, “In mainland North America, our ancestors substituted sweet potatoes for yams, swapped collards for tropical greens, added squashes and cucumbers, and made a few other adjustments, while retaining okra, sesame, watermelon, muskmelon, taro, Bambara groundnuts, peanuts, hot peppers, tomatoes, eggplants, and more. Millet and sorghum crossed the oceans, as did balsam apples and pigeon peas. We have one of the longest and most sustained edible gardening heritages in the Americas, and that heritage tells the story of the entire region surrounding the Atlantic.”

As African-Americans continue to innovate soul food, its significance is clear. Dr. Patterson proclaimed, “We share more than food. We share purpose, consideration … we have accountability to ourselves and that of the community. It nurtures our connections with each other.”

That is soul food.

Image of collard greens in a bone white and ocean blue ceramic pot taken by Barbara Jackson was sourced from Pixabay on December 12th, 2024.

Sources

Image of Chef Anthony T. Head, from “Anthony T. Head” page of Facebook, accessed December 14, 2024.

“African American Heritage – The Great Migration”, National Archives, accessed November 25, 2024.

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration

“The Great Migration” map, Students of History, accessed December 14, 2024.

https://www.studentsofhistory.com/the-great-migration

“The Humble History of Soul Food”, Black Foodie, accessed November 25, 2024.

https://www.blackfoodie.co/the-humble-history-of-soul-food

Michael W. Twitty in Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh African, Caribbean & Southern Flavors Remixed by Bryant Terry, 2014.

“Everything But the Oink”, Pork Checkoff, accessed November 26, 2024.

https://porkcheckoff.org/pork-branding/facts-statistics/everything-but-the-oink

“Soul Food”, African-American Registry, accessed November 25, 2024.

https://aaregistry.org/story/soul-food-a-brief-history

“Culture and Food Practices of African-American Women with Type 2 Diabetes”, National Library of Medicine, accessed November 24, 2024.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28929866

“Black People, Heart Disease and Stroke”, American Heart Association, accessed November 24, 2024.

Image of Alonzo Patterson III, MD, PriMed Physicians, accessed December 14, 2024.

https://www.primedphysicians.com/provider-listing/md-alonzo-patterson-III.html

“An Illustrated History of Soul Food”, Museum of UnCut Funk, accessed November 28, 2024.

Image of collard greens in ceramic vase, Barbara Jackson, Pixabay, accessed December 12th, 2024.

https://pixabay.com/photos/greens-collards-veggies-vegetable-646810